Decoding PLG: Navigating efficiency and growth in today’s software market

The recent slowdown in software markets is a compelling event for our industry to reprioritize efficient growth, which often means shrinking sales and marketing (S&M) budgets. Many leaders are naturally wondering if product-led growth (PLG) can help.

It can — but only if strategic analysis confirms that PLG plays to your company’s strengths. In this article, we define PLG and introduce a strategy selection framework to kickstart this analysis.

Defining PLG based on our journey at Datadog

We were fortunate enough to lead revenue growth and product strategy for Datadog, which has been labeled a blockbuster PLG success story. But, PLG isn’t a term we used within Datadog to describe our model. Talking to peers, investors, and founders, we heard confusion and disagreement. Does PLG imply having a product that sells itself? Well, humans were integral to Datadog’s success. We had a sales team involved in almost every deal, along with marketing, customer success, and technical resources. Even as the conversation around PLG has sharpened, we still feel that there is a gap in making sense of it all.

We spoke to executives and reflected on our own experiences. While we aren’t particularly fond of the term “PLG,” we see it as a new operating model for modern software companies – one that intentionally aligns product development and revenue growth in ways that previous generations of software businesses did not. Today, product features don’t just satisfy customer requests; they create new usage patterns that revenue teams can leverage. Sales teams don’t prospect in a silo, they are tactically fed usage signals directly from the product. If DevOps is the cross-functional fusion of development and operations, PLG is the cross-functional fusion of product and revenue.

If DevOps is the cross-functional fusion of development and operations, PLG is the cross-functional fusion of product and revenue.

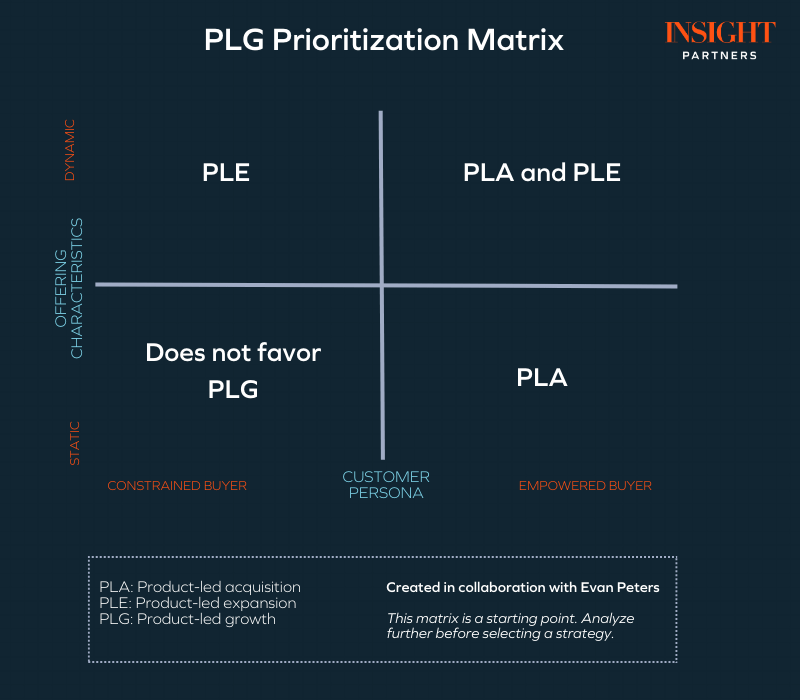

There are two types of PLG powering this new operating model: product-led Acquisition (PLA) and product-led expansion (PLE). They are not mutually exclusive, and you can pursue both simultaneously or in sequence.

To assist you in getting started, we developed a framework.

Leaders need to differentiate between product-led acquisition (PLA) and product-led expansion (PLE)

Each model can drive increased efficiency, but not for every company. Some companies can benefit from both. Selecting which to lean into is a prioritization exercise.

PLA strategies target efficiency landing customers by reducing buying barriers

Much has been written about PLA models. Broadly, these models reduce buying friction by disintermediating traditional sales processes.

Among other tactics, these models drive customers to self-onboard to a trial or free-tier and then convert to a paid plan with little revenue team support or just swipe their credit card. The result? You can leverage fewer human resources to acquire more customers. Examples of companies using PLA include Atlassian, Tailscale, Postman, Canva, and Figma.

However, creating awareness of your product isn’t free. And like any acquisition tactic, the return on invested capital (ROIC) eventually diminishes as the market becomes saturated.

PLA feels like alchemy: turning code directly into users and/or revenue. We see founders default to PLA because it plays to the strengths of the early team. However, ALWAYS prove product-market fit through founder-led sales, even if in tandem with PLA tactics. Product-market fit is typically confirmed through direct customer interactions.

Moreover, the bar for PLA can be higher than for sales-led acquisition. You need smooth self-service onboarding, meticulously detailed documentation, clear messaging, and community development to successful launch a new product using the PLA model. Why not drive a few design partners to a contract before polishing the product for full PLA readiness?

PLE strategies drive efficiency after the initial sale with long-term product execution

PLE describes an offering built intentionally to empower customers to self-discover, manage and realize additional value after their initial onboarding. Lower friction means revenue teams apply a lighter touch to upsell, saving time and expense, which is reinvested into more research and development (R&D).

PLE tactics include launching new, but connected products (e.g., Datadog), building a third-party application ecosystem (e.g., Slack), or introducing new features/products that increase consumption of the core offering (e.g., AWS). These investments in R&D raise the revenue potential of each customer while reducing the selling effort required to get there. In this way, PLE is a leveraged investment that pays back on a longer time horizon and calls for different skills and very sharp leadership within your revenue org.

You’ll also need to fund the journey to achieving your PLE strategy. For example, Datadog envisioned a PLE strategy, but sold only one product for five years before launching its second act. While building a platform, Datadog used its top-right matrix position to scale with a combination of marketing, customer success, sales, and PLA.

Launching multiple successful products is a rare achievement, so PLE can be a riskier strategy. We all know the story: fiefdoms and technical debt hinder innovation as companies scale. It’s harder to execute the longer you wait to get started. But for many companies with the right leadership and R&D capabilities, PLE is a great investment. Importing PLA tactics like free trials for new products can help you achieve your PLE strategy.

Use the PLG prioritization matrix to classify your offering and buyer

Our framework helps teams of all stages answer the first-order questions you’ll face: can PLG even work given the intrinsic characteristics of our product(s) and customers?

We emphasize that this matrix is only a starting point. For example, a company in the top right can make use of PLA and PLE. But that doesn’t mean they should.

Product resources might be spread too thin, or capabilities may point to better execution of sales-led landing plus PLE down the line. Furthermore, the PLG matrix is a tool for aligning your board members and stakeholders, enabling everyone to visualize the path to growth through the essential interplay between your go-to-market (GTM) strategy, your product offering, and your target buyers.

Start by assessing how your target buyers behave

Constrained buyer: Although their influence varies, your end user will almost always lack purchasing power, so you’ll need to work through an economic buyer who signs the checks. This is often the case in regulated industries or mature companies where the procurement process is formalized. For example, selling SOX compliance software almost always revolves around convincing the economic buyer at a financial institution. Note that constrained buyers likely do not own implementation either, so quick time to value is essential for ensuring the product is prioritized among other projects.

Empowered buyer: The individual who uses your product is free to make quick purchasing decisions, such as swiping a credit card or driving a purchase order. They might try your product in a low-stakes environment before bringing it into their workplace. For example, Tailscale’s users often first install the easy-to-use VPN to secure smart devices in their homes before bringing it to work to connect remote teams.

Keep in mind that, at some point, you will need to sell to both constrained and empowered buyers in your market, including small and medium-sized businesses (SMBs) and enterprises. You can still drive a groundswell of influence up to the empowered buyer at the user level — this dimension is a spectrum.

As a rule of thumb, it’s best to concentrate on the buyer persona you aim to win over in the next 6-12 months. Just like traditional sales, it takes time to develop your PLA strategy.

Next, evaluate whether your offering creates an opportunity for low-friction expansion

Leaders should evaluate their offerings on a reasonable timeframe along the spectrum from static to dynamic. Given enough resources and time, most offerings can grow to be dynamic. We recommend that leaders position themselves based on their 12-24 month roadmap and resource capacity.

Static offerings: The value of a product is merely the sum of its individual parts. Single products tend to be static, but so too are multi-product offerings that are not seamlessly interconnected and don’t compound value for customers. Take Salesforce and Tableau, for instance. While Salesforce owns Tableau, the product experience between the two is not dynamic — using Salesforce does not naturally guide you to Tableau to continue your workflow. Consequently, static offerings are not well-suited for achieving PLE. Instead, your revenue team will be pushing your customers towards new products with separate sales cycles rather than efficiently leveraging their current usage to capture new value organically. Static offerings can work for PLA, as individual products may appeal to empowered buyers.

Dynamic offerings: Dynamic offerings are inherently viral thanks to their deliberate design. Landing a single product can create a groundswell within an organization. Tight integration across multiple products organically creates cross-sell. Or, the offering is a platform for third-party developers.

Postman uses many of these tactics. Most notably, customers can publish their APIs on the Postman API Network, which creates a funnel for new users to try the free version of Postman.

Datadog creates virality using the extensible nature of the platform. Datadog is used by engineers who instrument their infrastructure to track technical metrics like CPU utilization and applications performance stats like latency and error rates. But it can also be instrumented to business-relevant KPIs like shopping cart click-through rates. When developers start experimenting, it attracts business users to start a conversation about how software performance impacts the business.

This phenomenon creates an accelerating “flywheel” effect. Incremental instrumentation of custom metrics drives increased consumption, as newly acquired business users request broader instrumentation across their eCommerce websites.

Even if the intrinsic characteristics of your offering/buyer fit PLG, dig deeper

The leadership team at Contentstack, a leading headless CMS and digital experience platform, underwent a thoughtful evaluation and weighed its internal capabilities and competitive dynamics to prioritize a sales-led approach despite fitting the PLA profile.

In the early days, Contentstack sat in the bottom right-hand corner of the PLG matrix, where the product fundamentals and target buyers favor PLA. The company’s focus was on empowered marketers, and the product had the potential to be a dynamic offering (which it has now become). The leadership team considered PLA, but their primary competitor, Contentful, was already heavily investing in PLA within the SMB segment. Contentstack faced a choice: either compete head-to-head for the empowered SMB buyer or find an alternative approach.

A clear-eyed assessment of their capabilities suggested that Contentstack would be more successful selling to enterprise personas. The company’s leadership had a background in the services world. Contentful’s awareness-building efforts in the SMB sector bled into the enterprise market, providing some lift to the product category. This created an opportunity for Contentstack to seize with enterprise sales. Additionally, why engage in direct competition with a strong competitor for a relatively small SMB prize?

In the short run, maybe this didn’t look “efficient.” PLA had been proven by a competitor. Contentstack needed to hire enterprise sales reps and wait for them to ramp. But, it saved a potentially costly confrontation with a strong competitor and set Contentstack up to move faster toward PLE as it bought time — and saved on capital resources — to develop a dynamic platform with new products like Launch (front-end hosting) and Automation Hub (full-stack automation).

There’s no counterfactual to test how Contentstack would’ve scaled by prioritizing PLA. But if our job as leaders is to invest thoughtfully amidst substantial ambiguity, that is exactly what Contentstack did. There was no guarantee of success, but it was a process-driven decision that started with asking the fundamental question: Does our positioning imply PLG can work? Well, yes it could. But digging deeper: is it the best way to win given the environment and our capabilities? The evaluation increased the odds of kickstarting a revenue flywheel precisely because it played to local strengths.

If the goal is efficient growth, patience is the way. Contentstack’s strategy relies on having some level of foresight into the future, including a roadmap for PLE with the sales org funding the journey. Even if the fundamentals open a PLG door, leaders need to be diligent about walking through. That diligence is the opportunity to focus and align revenue and product teams under a common north star. That’s the magic. It’s in the work.

Leaders who select a PLG strategy must align the entire company to customer value

The leadership team at Datadog, a leading cloud observability and security platform, envisioned a multi-product (PLE) platform and aligned revenue organization from the earliest days – years before they launched the second product.

Each product within Datadog’s portfolio includes hooks and workflows that transcend multiple offerings, incentivizing users to adopt multiple products to maximize the benefits. Right-clicking on any element in Datadog unveils a multitude of telemetry and views to explore, some of which require new onboarding and trigger a free trial for an independent SKU. Additionally, many of the key differentiators of new products leveraged the underlying platform or cross-pollinated features from other products.

A crucial aspect of enabling unified workflows was adhering to a common data model. Consider a user who subscribes to infrastructure monitoring and application performance monitoring (APM) but not log management – all separate SKUs. If they encounter an error or latency issue that requires investigating logs, they might open a competitor like Splunk and attempt to formulate a query. However, this entails context-switching and writing queries in a different language. Moreover, they may discover that the specific tag they use for a collection of infrastructure is only available within Datadog and not in Splunk. In contrast, with Datadog, the user can simply right-click on an APM trace to access the associated logs seamlessly.

Datadog intentionally aligned its selling and R&D to support this pattern of product adoption, rallying everyone behind the ethos that value should be monetized when it is created. Datadog’s consumption model and product design put the customer in control of how they derive value.

Hence, product investments were tailored to leverage revenue team cycles by continuing the sale — showing users more and more value — after the human conversation ends. In turn, the revenue teams support customer-led discovery by landing right-sized deals without rigid contract constraints. Because this produces a lighter touch from the human teams, saved cycles are reinvested into landing more new accounts or educating customers on newer products.

At scale, this process produces S&M expense savings, which are reinvested back into more R&D.

Datadog embedded dynamic offering characteristics into its first product like the custom metrics feature, which allows customers to define measures tailored to their specific needs. Combined with PLA tactics and aligned revenue teams, Datadog was able to test drive PLE from the earliest days before building up to a multi-product platform.

Datadog’s journey stresses the importance of company-wide alignment to succeed at PLE.

Read: How PLG companies can scale efficiently by transitioning to hybrid sales

Follow an analytical process to select PLG, but don’t stop questioning it

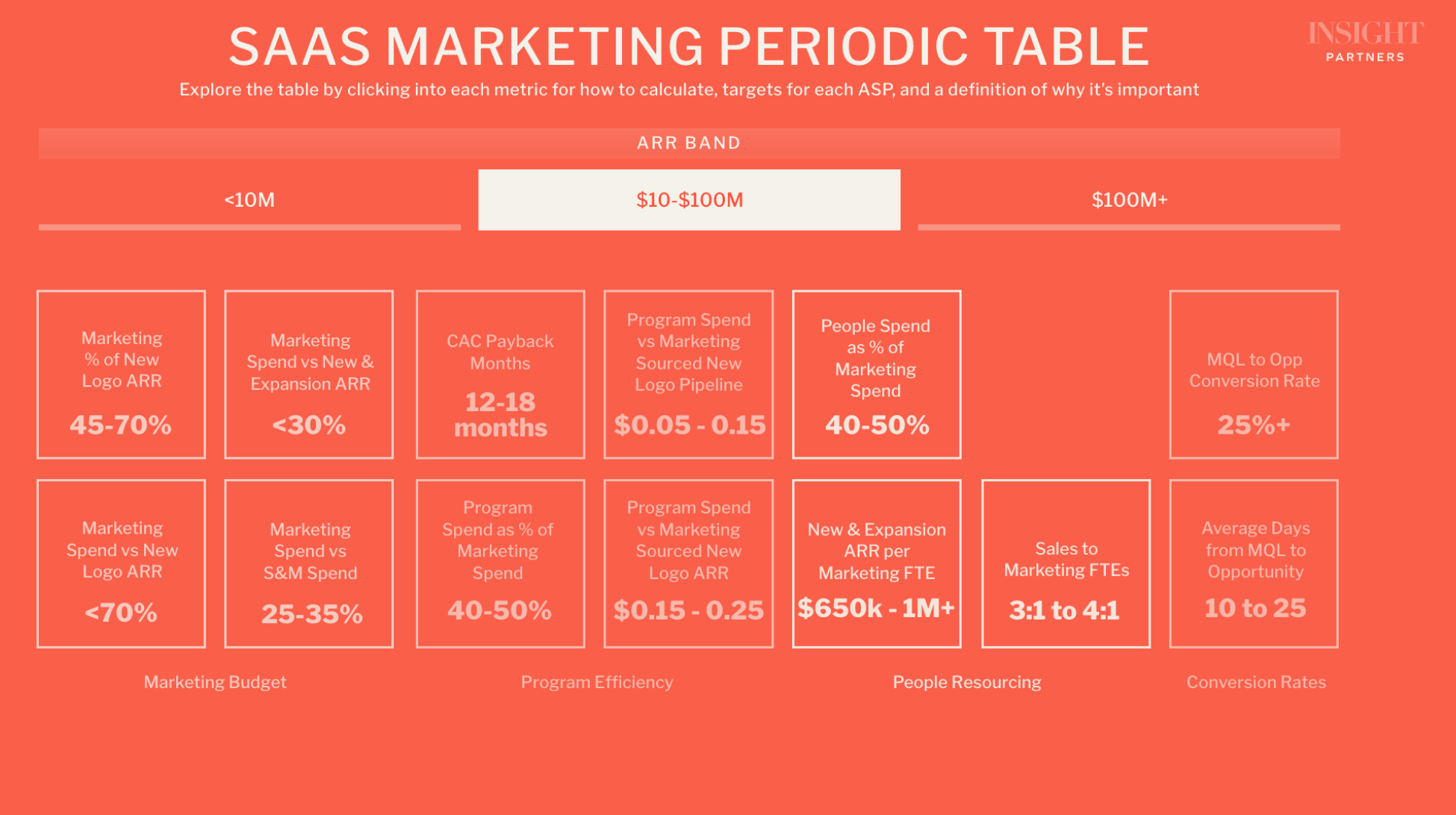

Halo effects and survivor bias tend to highlight successful PLG outcomes at the expense of the true lesson. We see too many companies running PLG playbooks (particularly PLA) without strategic clarity. This can lead to massive inefficiencies like overspending on marketing.

Truly exceptional software companies achieve greatness by making numerous principled decisions and learning from their mistakes, not PLG alchemy. These companies are led by leadership teams with a deep understanding of their customers, market, competitors, and their own capabilities. They are intentional about building synergy between R&D and revenue generation, and they continuously re-evaluate their strategy.

Starting with the PLG matrix and proceeding into deeper questions about the company and its environment, leaders can unlock something extraordinary: a company blueprint for efficient growth that provides clear guidance to product and sales teams.

Evan Peters is a revenue, strategy, and operations executive for software and technology businesses.

Contentstack, Tailscale, and Postman are Insight portfolio companies.