Accelerating outcomes with customer value mapping

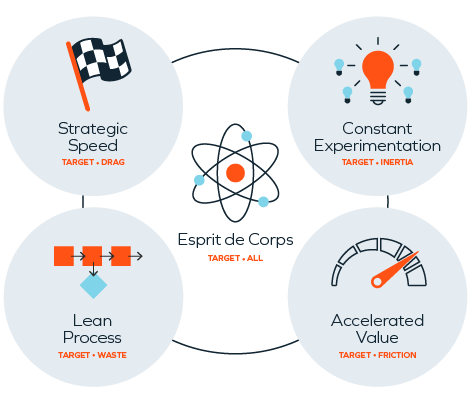

In our previous article introducing the S.C.A.L.E. model, we noted that the principle of accelerated value is primarily focused on reducing unnecessary friction in the customer experience as a means to improve an important leading process indicator: time to value. Shrinking the time it takes for customers to realize value is a universal challenge for SaaS ScaleUps.

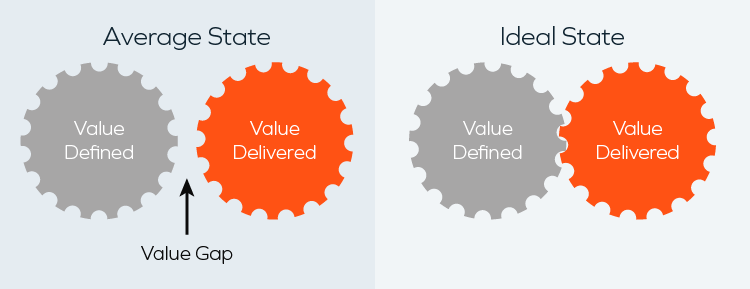

Putting the principle of accelerated value into practice can be thought of simply as aligning two constantly moving gears: value defined and value delivered. From our experience working with ScaleUps, we have realized a common issue that must be addressed: too much space between, indicating a value gap in need of closure to avoid loss. This is what AWS sales and marketing chief Matt Garman was referring to when he said at Amazon’s re:Invent conference that, “the biggest obstacle to growth is the failure to understand and align with customer-desired business outcomes.”

Let’s look at each gear before introducing a practical tool for closing the value gap.

Defining value: Jobs-to-be-done

One of the most difficult concepts for anyone in business to understand is that no customer really wants your product; they want to get their most important jobs done, and need a way to maximize their effectiveness in doing so, preferably in a manner faster, cheaper, and simpler than how they’re doing it now. To the extent your offering does that consistently, customers will stick around.

In the December 1942 edition of the Somerset American, the Provident Mutual Life Insurance Company ran the following advertisement:

HARDWARE STORES REPORT THAT OVER ONE MILLION MEN BOUGHT ONE-QUARTER INCH DRILLS IN ONE YEAR. NOT ONE OF THOSE MILLION MEN WANTED THE DRILLS. THEY WANTED QUARTER-INCH HOLES IN METAL OR WOOD. PEOPLE WHO BUY LIFE INSURANCE DON’T WANT LIFE INSURANCE; THEY WANT MONTHLY INCOME FOR THEIR FAMILIES.

The hole-not-drill concept of value stuck amazingly well over the years, so much so that in the December 2005 issue of Harvard Business Review, the late Clayton Christensen and Intuit founder Scott Cook published an article entitled Marketing Malpractice: The Cause and the Cure, crediting the idea to Christensen’s marketing professor, Theodore Levitt, writing: “The great Harvard marketing professor Theodore Levitt used to tell his students, ‘People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole!’ Every marketer we know agrees with Levitt’s insight. Yet these same people segment their markets by type of drill and by price point; they measure the market share of drills, not holes; and they benchmark the features and functions of their drill, not their hole, against those of rivals. When marketers do this, they often solve the wrong problems, improving their products in ways that are irrelevant to their customers’ needs.”

The article went on to introduce a new and better way to think about products and markets, one that looked at needs from the customer’s perspective. “The structure of a market, seen from the customers’ point of view, is very simple: They just need to get things done…When people find themselves needing to get a job done, they essentially hire products to do that job for them. The marketer’s task is, therefore, to understand what jobs periodically arise in customers’ lives for which they might hire products the company could make.”

Soon after the article came out, the notion of products being hired for a specific job became widely known as “Jobs Theory.”

The jobs framework

ThejJob that we hired jobs theory to do in this article is to define value from the customer’s perspective to maximize acceleration of value.

We have worded the above job carefully. It has two major components: the job-to-be-done (define value from the customer’s perspective) and a desired measurable outcome (maximize acceleration of value).

Note how closely this mirrors the structure of OKRs — objectives and key results, which most tech firms are familiar with. We suggest using the following guide to define value from the customer’s perspective:

Step 1: State the Job-to-be-Done

What is the customer’s main objective? A job-to-be-done can and should be stated very simply using a verb, an object of the verb, and a word or two about the circumstances, context, or situation. In the example below, the verb is protect, the object is important information, and the circumstances or context relates to exposure.

Step 2: State the Desired Outcome

What key result is the customer hoping to achieve? A desired outcome can and should be stated very simply using a change vector or delta, the measure itself, and a few words to add clarity and focus. In the example below, the delta is minimize, the measure is loss, and the focus is confidential company data.

| JOB TO BE DONE (Main objective) |

DESIRED OUTCOME (Key result) |

| Verb + Object + Circumstances | Delta + Measure + Focus |

| Example: Protect important information from exposure | Example: Minimize loss of confidential company data |

Notice that this structure does not mention or even suggest a solution. In the above example, a company might retain a security firm, subscribe to a SaaS security platform, build an internal security team, require special clearances, install physical identity measures, or employ sophisticated encryption.

It is imperative to understand that while solutions come and go, a customer’s Job-to-be-Done remains stable over time—past, present, or future, it remains essentially unchanged.

There are a few more things to keep in mind when defining value from the customer’s point of view using this framework:

- Like an OKR, a clear start and stop are required; you should be able to at some point definitively answer the question “Was this achieved?” Steer clear of stating Jobs with words like maintain, support, help, manage, and the like, simply because it will be difficult to know when the Job-to-be-Done is, well, done.

- The main job is not the customer’s job title or description, nor is it a simple to-do item or task. “Go to the grocery store” is not a main Job, “get groceries for the week” is.

- Avoid conflating the job-to-be-done with the desired outcome; remember that the first is an objective, the second is a result. It may help to think of desired outcomes as needs…designers certainly do! Desired outcomes are not immediately obvious or well-articulated by customers, but they can be inferred from observation and confirmed through interviews, stories, and experiments.

- Never forget that customers are far more loyal to the job than your product or service. If something better, faster, simpler, and/or cheaper comes along, they will shift over to that solution, assuming switching costs aren’t prohibitive or painful.

From proposition to promise

One additional note on defining value concerns the standard business practice of creating a value proposition. We suggest going a step further to create a “value promise” for each specific customer and their job-to-be-done. This helps break up a one-size-fits-all value proposition into something that is a bit more job-tailored. Using the example in the rubric above, we can simply mash up the job and desired outcome: “Anubis protects your important information from exposure so your chances of losing confidential company data are minimized.”

This format sounds and feels more like a personal promise to an individual and creates an expectation of a successful job completion and desired outcome achievement. And if we know anything about customer satisfaction, it is the delta between expectation and outcome.

Give the value promise a try. We find that instead of one universal value proposition, it helps to have several value promises, each tailored to a unique job performer, be they buyer, customer, or end-user.

Delivering value: The customer value map

In a short e-book by Gainsight called 10 New Laws of Customer Success, the authors advise that, “It is no longer enough to have a customer journey… you must simultaneously consider their most urgent needs and their long-term goals. The traditional, linear lifecycle doesn’t make sense for today’s customers. A linear engagement model or customer journey from marketing to sales to renewals fails quickly.”

We agree. In working together several years ago in an effort to optimize customer-experience improvement, we realized that the key artifact of the conventional customer journey, the customer journey map — usually a nicely designed menu of all the things a company wants a buyer, customer, or user to ideally do or consume throughout their relationship with a brand — was obsolete almost as soon as it was published. The actual experience customers were having did not reflect the pretty map, because customers and markets constantly change, meaning, the territory covered by the map had shifted and no longer looked the same.

We wanted something more useful. It had to be more dependable, more stable, and, paradoxically, more dynamic and easily updated in real-time. It had to point us toward areas in need of immediate attention, namely where we were missing the mark in providing value to customers on their terms.

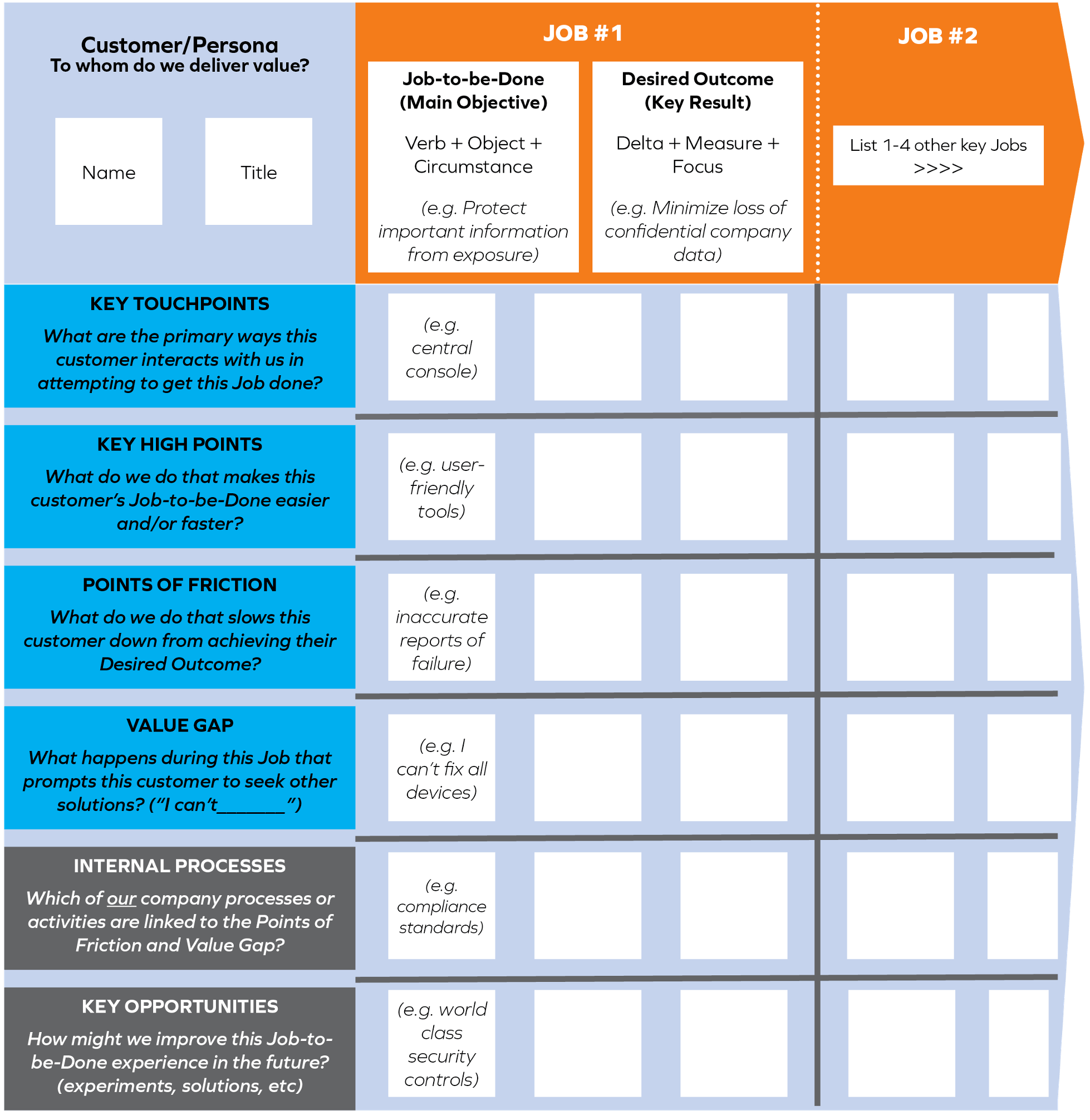

Realizing that the customer’s main job is stable over time, we created what we now refer to as a customer value map, an overlay of jobs theory on the key inflection points in any customer experience that we constantly use to guide value-acceleration efforts. Instead of using traditional demand-generation phases, we anchored everything to key customer jobs. We then made sure to reflect current touchpoints, high points, points of friction, and gaps in value delivery. We also wanted to pinpoint our internal processes and activities that were linked to the specific customer’s Jobs. Finally, we also wanted to note any thoughts on how to improve those Jobs.

Armed with all of this, we could produce a solid list of fresh insights that provided a point of origin to begin closing the gaps and guide the effort to accelerate value. A good map shows you where you want to go and the various routes of getting there, but it only works when you first know exactly where you are.

A snapshot of our current basic customer value map framework is shown here.

Touring the customer value map

Navigating the customer value map is simple, and completing it requires little in the way of special facilitation. As long as everyone understands the basic Jobs-to-be-Done framework described earlier, the rest is fairly self-explanatory.

Let’s take a quick tour.

The customer value map is basically a matrix that begins with the customer whose experience we want to map. Personas and profiles, if they exist, are helpful, but we always recommend inviting actual customers to these kinds of sessions, because it is always illuminating, and it saves time having to validate the output with real customers in the future. We always recommend completing a customer value map for a certain customer with a team of people who know that customer best. If that’s not possible (and it often isn’t), we always recommend completing a customer value map for a certain customer type with a team of people who know that customer best.

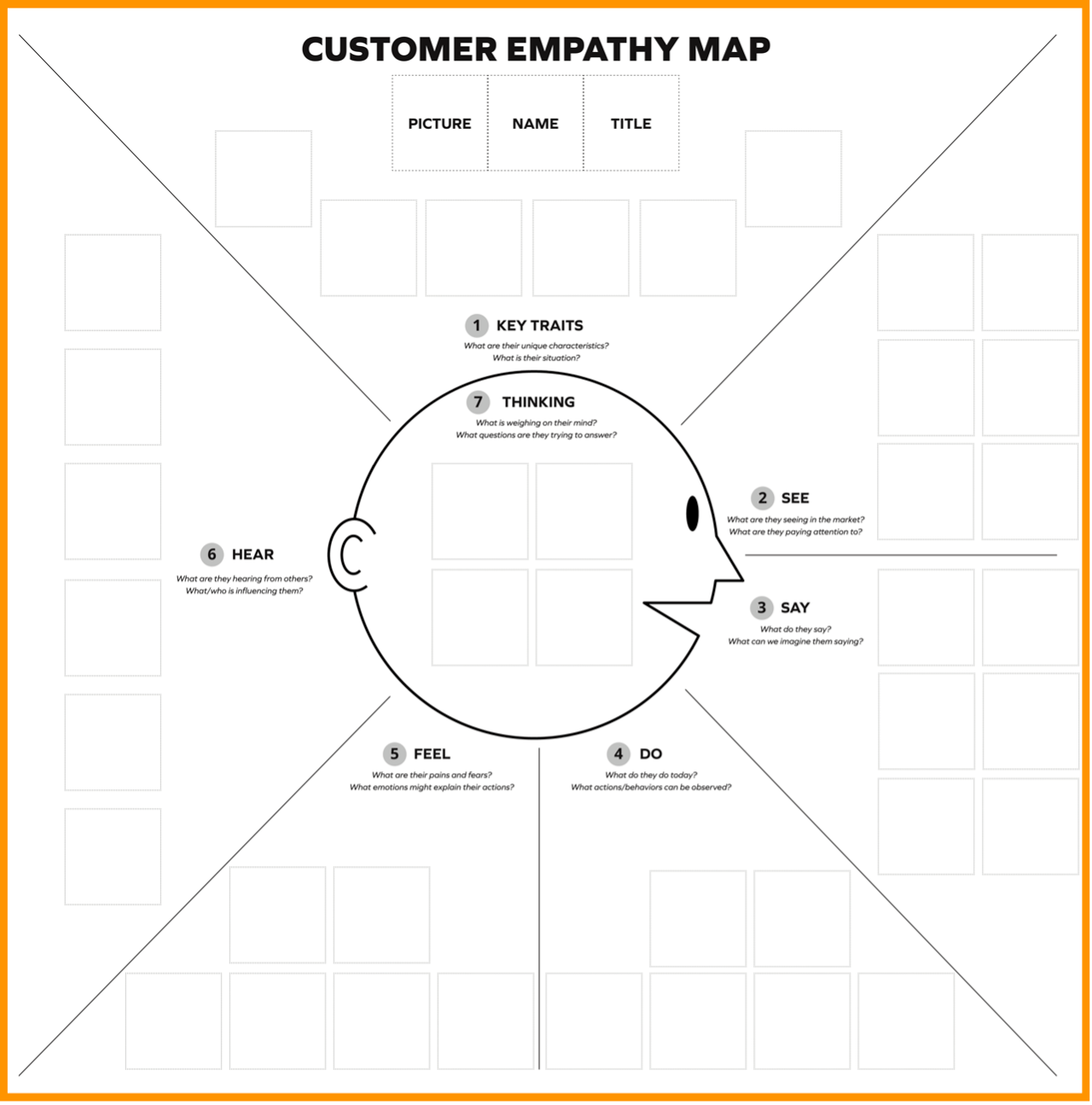

Either way, we always spend a few warmup minutes completing a basic empathy map for that customer, quickly sketching out their general characteristics, and answering several key questions: What is this customer seeing, saying, doing, feeling, hearing, and thinking? This gets people out of their own heads and into the head of the customer. Empathy map templates are widely available, and the one we use is shown below.

Once the empathy map is complete, we begin working horizontally across the top of the customer value map, left to right, mapping the key jobs-to-be-done and desired outcomes that this customer is hiring your solution to do. In most cases, there are one or two main jobs and a few supporting jobs. Once the top row is complete, we work vertically, completing all six left-hand categories before moving to the next job. Do not work by row — work by column — focusing entirely on one job at a time. This is critical to avoid falling back into old ways of thinking about an experience. Specificity breeds insights, but generalization doesn’t, at least in this case.

Moving down the left-side map coordinates, paying attention to the word key, focus on the top one-to-three responses in the six left-side categories:

- Key touchpoints. Multiple points of interaction between the customer and your product undoubtedly exist for any Job. What are the primary ones? Which ones does the customer employ most at this point in their journey to getting the specific Job done?

- Key high points. There are reasons you’re successful—moments of joy you and your product create for the customer, making getting their Job done easier and/or faster—what are they?

- Points of friction. In the context of the Job, how are you slowing down the customer from achieving their Desired Outcome?

- Value gap. In every Job, there comes a point of inflection, a critical moment or problem that can determine whether the customer leaves or stays with your solution. This is a value gap. From the customer’s point of view, these value gaps often sound like, “I can’t do X,” or “It’s really difficult for me to do Y.” These are solvable, but they must be documented.

- Internal processes. The last two items are a lighter shade of gray, just to emphasize that these are from the perspective of your processes and activities that are linked to the Points of Friction and Value Gap. These act as locators and focal points for the final category.

- Key opportunities. Using Points of Friction, Value Gaps, and Internal Processes output, what can be done to improve this Job for this customer? What can be built; what experiments can be run?

Get your copy of the customer value map

You can get a PDF copy of the customer value map here.

When you have completed customer value maps for all of your key customer personas, know that you’ve taken a huge step forward in the effort to accelerate outcomes.

Learn more about applying lean principles to scale by reading our book, out now: What A Unicorn Knows.

Gainsight is an Insight Partners portfolio company.